Lisa Berger: "The profession of a documentalist is a good place for people with a passion for history. It gives us the opportunity to contact people who have risked their lives to document turbulent times."

This month we interview Lisa Berger, film researcher. We talk to her about her work as an audiovisual documentalist and about the ins and outs of her profession.

How did you come to the world of audiovisual and why did you decide to specialize as a documentary researcher or documentation professional?

I graduated at an alternative university, Hampshire College, in Massachusetts, USA, where we designed our own programme. There, I followed my passion, which was Women’s Studies; the history of social movements, especially those of women. I attended a seminar on anarchism, run by Martha Ackelsberg, author of the book Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women, (ed. AK Press). The case of the Spanish libertarian movement is the only moment in history when an anarchist revolution has been experienced on such a large scale although for a short period of time. It is admired and studied a great deal outside Spain. I was so inspired to know that there had been a group of women who in practice connected the anarchist revolution to the emancipation of women that I wanted to know them first hand. I wanted to find out for myself whether the ideal of the social revolution truly succeeded in transforming the role of women. I was interested in what it was like to experience that, not in the achievements or the numbers. I wanted to talk to them. I needed an excuse. Making a video documentary is a way of giving something in exchange. I therefore studied the techniques to document the oral history of women within my study programme and then took a course on video documentary filmmaking outside the university. As a final project, I came to Spain in 1981 to make a radio documentary about the feminist movement. After completing my degree, I received a grant to spend a year in Spain and make a documentary which was then ... All Our Lives.

The fact that I had made this documentary opened the doors to work as a researcher and crowd coordinator for Land and Freedom, directed by Ken Loach. As a result of this work, they called me from the CCCB and, from there on, other producers also called. Before being a documentalist, I worked for many years as a producer, production director, production manager, etc. Production work is very stressful; I had a great deal of responsibility and very little recognition. They only think about the person in charge of the production when there is a problem. I preferred it when I could devote myself to documentation because I could concentrate on a single task. The truth is that only recently is the profession of documentalist beginning to be recognized here in Spain.

What do you think are the main characteristics that someone devoted to your profession must have?

They must have a broad general culture, know above all the history of the 20th century, be orderly, patient, meticulous, proactive, be able to work in a team and alone and have studied or worked in film / TV in order to have visual and technical knowledge of formats, be able to describe the types of shot, etc. It is important to know something about editing in order to know which shots can be used to narrate the story in each case.

What are the main functions of the film researcher?

I like the fact that you describe the position in English because it’s clearer like that. The researcher looks for the images, while a documentalist in Spain may have studied library science and know how to order material in an archive, but not have any idea about where or how to look for it. I believe that it is better to have studied or to have undertaken production or any aspect of audiovisual creation than to have studied library science/documentation. But this is how it has been organized until now in Spain. This is the case because I understand that my function is not only to locate the material that the director wants, but to persist with the archive or television until they send you the quotation or material. It appears to be different to work as a documentalist in television because there they only search, while in the world of the project-based freelance, as researchers we are expected to get to the end of the process.

So the work consists of locating the material which best illustrates the concepts of the script; if they do not exist or are outside the scope of the production for time or money reasons, to propose alternatives, and then to organize your time to work autonomously to obtain the material with the calendar and budget established by the producer.

What sources of information do you consider to be essential for your work?

To a great extent, the sources depend on each project. What is interesting about this job is that no two projects are the same; I always learn something new. It is important to know what is available which is free from royalties / in the public domain for commercial use and what is not.

What is the first thing that you do when you confront a new project?

I ask about the overall budget foreseen for the royalties and what rights are needed. Then I break down the script with the archive images necessary. Afterwards, I make a master document in which I put the sources where each image could be found. I make one list per archive and I contact them, explaining what I am looking for, and what rights we need: the territories, duration, means.

What is a normal working day like for you?

It depends on each project and on the phase that it is in, but normally I can deal with some 2-3 archives per day. Each archive has a procedure which must be followed to the letter. This quantity doesn’t seem very efficient, but there are international archives which require you to fill in an online form to request the rights and another for the copy. It is not sufficient to send them an e-mail explaining what seems to be important to you.

What attracts you the most about this work?

The challenge of researching; you don’t know whether you are going to find what they are asking you for, but you know that, if you don’t, you will find a solution. I love entering the content, having to read articles, contact historians, people who work with NGOs devoted to historical memory, or people passionate about very specific issues.

It is curious because often the producers ask the people working in production to carry out the documentation when, according to the budgets of the ICAA, documentation forms part of the script department. It should form part of the scriptwriting process: knowing which images are available to illustrate the ideas that you are writing, not waiting until the editing phase to call a researcher with the pressure on time that this represents. Then you have to modify the script if there are no images to illustrate that point.

And what difficulties do you usually come across in your profession?

The main one is the lack of knowledge of the intrinsic complexity by the producers in order to carry it out and the lack of respect for the people who do it. Even when they look for a researcher with proven experience, you have to fight to defend common sense concepts as basic as the fact that it is not possible to obtain everything that a director wants. They do not always accept that they have to set priorities. You have to be realistic with the time available. The advantage that experience gives is knowing how much you can obtain in order to be able to organize your time in the most productive way possible. But the other professionals need to trust in the criterion of the researcher in this respect. That is where the gender difference is noted the most in this profession. Very often, the directing/script and editing team are men and the production and documentation team are women. I have found that this fact influences the lack of respect for the documentation work. We are expected to be committed 150% of the time, without looking at what time it is. On the other hand, when I try to turn the problem around, rationalize the work to achieve a work-life balance instead of putting in hours, they do not tend to be so receptive. You can do this when you are young, but it is not sustainable or desirable as a lifestyle.

As I mentioned earlier, I began studying history at university, and only toward the end did I realize that I didn’t know what I would do with this education professionally. After thinking about it a lot, I believe that the profession of a documentalist is a good place for people with a passion for history. It gives us the opportunity to contact people who have risked their lives to document turbulent times. It is important to take care of the relations with these sources, to respect their story. If you do not keep your word, such as for example by sending a copy of the final programme, they will not give you their archive again in the future. On numerous occasions, the owners treated me with suspicion because the people who asked them for material until then did not keep their word. I had to convince them that I hope to continue in the profession for many years and that it suits me to be on good terms with everyone.

Has the fact that you have been a director and also a screenwriter of documentaries helped you in your work as a film researcher?

Of course. I can put myself in the director’s shoes and try to provide them with the best material in order to tell the story that they are trying to tell. I would add having being a producer in order to know how to fulfil a budget and be perseverant. This experience has also provided me with personal contacts who help me to obtain less visible or accessible material.

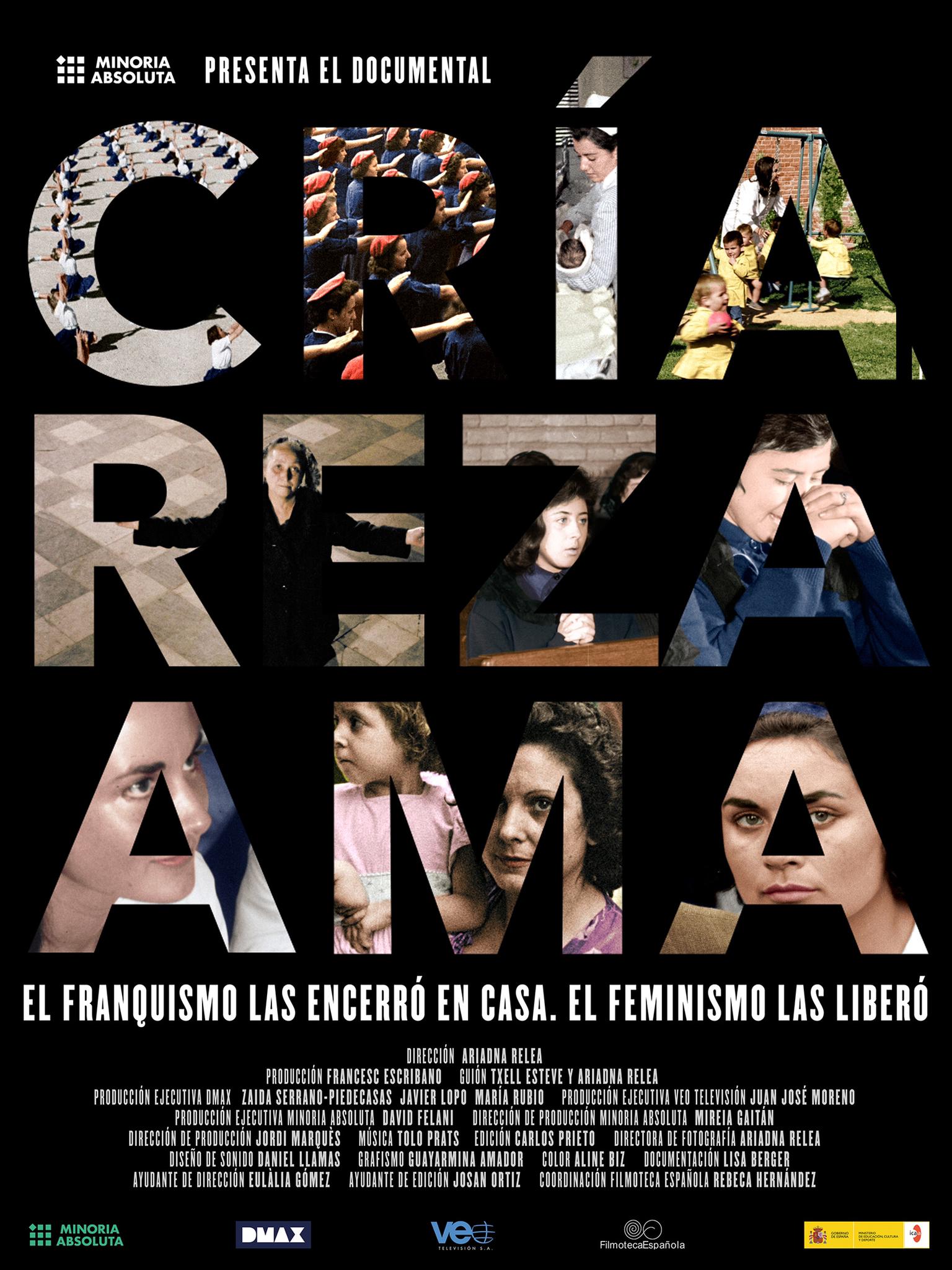

Your last work was Spain in Colour: Spain after the Civil War, the Franco Dictatorship in Colour. Tell us a little about the project. How did you come to it and what did your work consist of?

Through a workshop in which I participated on Archival Research during the Memorimage festival in Reus, the production company contacted me for an interview. It was a good sign that they selected me in July to begin in September. Normally, they call me to begin on the next day and it is difficult to organize your life like that. I love working on a series because it gives you the luxury of time. I can request material from a public archive and wait for the two months that they take to reply while looking for other things. With a documentary, we do not have this time. This allowed us to work in depth. With this series, the script/directing team had already invested one year in research before I joined. It would have been ideal if I had joined earlier. Even so, I worked on the series for more than one year. Out of the total of 15 chapters, there were eight with archive material which I looked for. My work consisted of locating material in movement, photos, the press and texts to illustrate the critical points of the script. The basis of the series was the No-Do collection in the Filmoteca Española. But this is the official version of the Franco regime. I was in charge of finding the material which demonstrated that what it said in the script which was critical of the regime was based on irrefutable facts. For example, if we said that Franco knew that there were Spaniards in the Mauthausen concentration camp when he said that he didn’t, we had to show an official document which proved that he knew. But Franco had destroyed many of the proofs of what his regime did. Overall, I consulted around 150 archives and I managed the rights to images or documents in 121 national and international archives.

How do the work flows operate in a documentary like this one? What are your relations with the rest of the team and with whom do you have most direct contact?

With other productions, I often work from home because the producers do not have enough space for me. In this case, I had to be in the production company because when I arrived we were already editing the first mini-series of four chapters (Spain after the Civil War, the Franco Dictatorship in Colour which consists of approximately one chapter per decade). I therefore had to be in constant communication with the director, editing and production. I am happy because the production was extremely well organized when I joined. There was a communication system with documents available online for the whole team and periodic meetings. The assistant director Eulàlia Gomez did her work so well that she optimized all the resources, including my time. I had her help to look for press articles from the time in online archives, which required a great deal of time, to know the precise story and to know exactly what we had to tell. Moreover, the documentalist devoted to the material in the Filmoteca Española, Rebeca Hernández, also went to the archives in Madrid which required face-to-face enquiries.

Did you come across legal barriers or any other kind of barrier on undertaking your work for this documentary?

I had to spend months negotiating with archives which in the end did not provide us with material, such as for example publishing houses which had the exclusive rights to photos of Franco which their legal team advised not to take the risk of selling to us 44 years after his death.

The Biblioteca Nacional de España, in relation to a front page of the newspaper Arriba, a publication of the Falange de las JONS, replied to us “the rights that you are requesting are not going to be possible. You are asking us for copies of the publication which have copyright in force. You would have to manage this with the holders of the copyright through the management bodies”. The Madrid Press Association, which transferred the rights of other newspapers to us, confirmed to me that the owner was from the “Movement” and the dictatorship is not in power any more. And when I asked for photos of a concentration camp from Santander, first they said that they could not provide photos which I had found on their website and then, when I insisted, saying that I would consult it with our lawyer, they said that there wasn’t any problem.

There are archives in Spain, above all public ones, which have “no” as the first answer. You have to know how to turn things round and remind them that their function is not only to conserve this material, but also to make it known, to be able to recover the historical memory. It would be very long to explain here everything that we had to do to obtain official documents from the General Archive of the Administration (AGA). I saw the difference in attitude when I obtained photos of maquis from an archive in Amsterdam. They sent me low quality material in one day when an archive here can take a month or more, if you insist a lot.

Having to colour in all the black-and-white images represented an additional challenge. I found two film libraries and one photographer who were not willing to consider transferring material from their archive in this case. It also represents an investment of more time and an additional complication when it comes to drafting the authorizations.

Another significant barrier is the copyright management companies. There were archives which sold us photos but their price did not cover the royalties. I had to find out whether we also had to pay royalties to each photographer or artist. In many cases, such as that of the official photographer of Franco, or a photo of a politician who died before the Spanish Civil War, conserved in a public archive, the price and the payment system for these rights were prohibitive. It is more difficult to tell the history of the country with these determinants.

What role do film libraries play in the work of film documentalists and film researchers? And private archives?

The other kind of difficulty to obtain archive material through the film library or public television is that they conserve the material but, very often, the researcher moreover has to ask for the rights from the private owners. The film library does not always have the up-to-date contact of the depositor. It has occurred that I ask for low quality material for which we pay the viewing and copying expenses, but when I request the rights then the owner does not want to sell them at a reasonable price, I cannot find them or they change their mind between the first and the last contact. Then, we have to change the editing. It is better to know whether we will be able to have the rights before showing the director or the editor something so that they do not fall in love with material that is not then available. Here, you need to find a balance between who has to invest their time in order to prevent any upsets: me as the researcher to ensure that five owners would agree to transfer their archive material when in the end we will only need one, or the editor on changing the sequence. Some film libraries do not give me the contact of the owner until we are sure that the director is interested in including it in the editing so as not to bother them unnecessarily. It is not, therefore, an easy or straight path for the researcher. As I mentioned with the public archives of documents and photos, not all the film libraries prioritize making their collections available to producers in order to disseminate the material that they conserve and they do not invest the technical costs that they charge in updating the techniques in order to make the collection more accessible to the real users. For example, I can access a great deal of material in the national archive of France, the INA, online from Barcelona, but, on the other hand, if a French researcher wants to access material in the Catalan or Basque film library online they can’t.

There are currently many audiovisual archives which have their collections accessible via the Internet. How have the Internet and the digital environment helped your work?

It is an advantage to have access to international archives online to be able to quickly assess whether material is of interest. But even the best archives do not have all of their historical material available online. It is always better to write to the commercial department to see what else they have. On the negative side, the assumption that everything is available online means that the producers do not budget enough time to moreover undertake an old-fashioned search, writing and waiting for a reply from the archives. This also means that everyone uses the same images, those that can be easily found. There is no longer a budget for a researcher to travel to any archive which they cannot reach on the underground.

Transferring an entire archive to digital format can also be a barrier. In the case of Televisión Española, they are converting their collection to digital but it is so big that they will take a long time to complete the process. They have already banned providing analogue material and, therefore, if your production needs to use material which has not yet been digitized, you won’t be able to.

What advice would you give someone who wants to devote themselves to this and who is starting out?

I recommend watching a lot of documentaries and looking at the list of credits at the end, going to art exhibitions to have a broad visual education. Everyone wants to hire someone with previous experience. In this digital world, it is now easier to make your own production and upload it to YouTube or another platform so that a producer can see what you are capable of. If you follow your passion, someone will see your work. Go to the numerous festivals that Barcelona offers, where the directors present their work and you can talk to them face to face.

I see a failing in the education system here. There are endless academic programmes on which you can study to be a filmmaker/director or even producer. But as far as I know none of them teach the profession of documentalist related to audiovisual. Young people graduate who are eager to be directors, but there are very few people who can go beyond their first film. It would be better to also teach the professions which do have opportunities in the world of work such as, for example, documentalist. I have proposed this on several occasions, but so far it has not been taken into account. The profession is so invisible that, when I wanted to be included in the online directory of professional of Catalan Films in this category, they told me that it doesn’t exist and that I should put myself in production. I told them no; it should be the other way round; they should create another field with the category “documentalist”. So I am tilting at windmills. In the directory of Dones Visuals they have created this category within the script area, as it should be. Let’s see if the producers learn to look for us there!

Within this context of lack of knowledge of the profession, I recommend that people who accept documentation work should agree on a tariff for a defined time, not for the project. Several times, they have tried to give me a flat rate per project according to which I could be working for three months for the salary that I normally obtain in one. I understand that the producers have to close their budget but we also have to eat. I therefore recommend stipulating a specific time for an agreed amount and that if the work takes longer – which always occurs due to changes in the script or something – then I leave a detailed list of the status of all the steps taken and someone from the production company continues to close them if they can’t pay me more.

In the 25 years that I’ve been working as a documentalist I have seen a lot of people do some documentation work and then abandon shortly afterwards. It is a tedious, not sufficiently well-recognized job. I believe that the profession of researcher should be better protected so that the documentalists can continue to devote themselves to it. In the workshop offered by Elizabeth Klinck in Reus, I discovered that it is not just a problem of Spain. From what she said, it is the same in Canada and France. We need to organize ourselves in an association in order to be able to resist and continue to contribute our knowledge and passion to explain the history of the country.

What are your next projects?

I am now preparing some documentary projects and one fiction project. I’m about to begin the documentation for a new television series. After the summer, I am open to proposals of projects in which I hope to learn something new each day.